I’ve been looking for information on memory recently, searching for ways to improve it. I know a few tricks (the peg system), but I don’t want to using a technique every time I try to remember something, I want general performance improvement. One way to improve the performance of a system is to learn how it works, and go from there.

This is where researchers Baddeley and Hitch come in (1). Most people think of human memory as being a passive storage space, but this isn’t actually the case. According to Baddely and Hitch’s working memory model, memory is an active set of processes (this is short-term, not long term memory) – when we first perceive something, it is ‘worked on’ in working memory. This is called encoding. Memories have to be encoded before they can be stored in long-term memory.

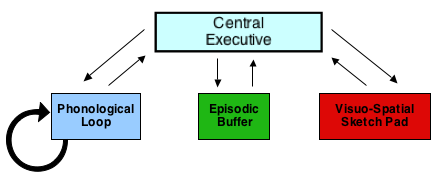

Baddeley and Hitch’s working memory model has a few separate parts to it, each processing different types of information:

Baddeley and Hitch: Working Memory

The central executive

This is the master controller of the working memory system. It’s functions are thought to include switching attention between tasks, selecting/ignoring stimuli, and activating necessary information from long-term memory. At the moment it’s unclear whether the central executive is one unitary mechanism, or whether it can be broken down into subsystems.

The phonological loop

This component holds speech-based information. It has two parts – a phonological store, which temporarily holds speech information, and the articulatory control process (ACT; the arrow in the diagram), which is the part that’s working when you’re talking to yourself in your head. The ACT is one way of getting information into the phonological store, but, information in the phonological store starts to decay after a few seconds. This is why to remember a phone number you need to keep repeating it over and over until you find a pen – you’re refreshing the decaying information by it by putting it through the ACT again.

Visuo-spatial sketch pad

Not surprisingly, this is the part that processes visual information. This might be from your eyes, recalling a memory, or creatively visualising something. If you’re seeing with your “mind’s eye,” or mentally manipulating an image, this is the part that’s working.

The episodic buffer

Information is encoded differently in the phonological loop and the visuo-spatial sketch pad, while the central executive can only process, not store. The episodic buffer is able to combine information from the above components into a single representation. This was added to the model only recently (2000), because a number of research findings were hard to explain without it. (2)

Anything useful in Baddely and Hitch’s working memory model?

Study tip

The phonological loop explains why it’s a really bad idea to listen to music with lyrics while studying. If you’re paying any attention to the music, it will enter the loop, and compete for encoding with whatever you’re reading – even if you don’t read ‘in your head’, looking at words visually seems to put them into the phonological store too. If you don’t encode the information, you won’t store it, and you’ll have a harder time remembering it tomorrow, let along in an exam.

Repetition

As the above stores only have a short capacity, one way of making encoding more likely is repetition. The more times you go over something, the better you’ll remember it. So read and re-read the thing you need to remember, in your head and out loud.

Chunking

Because the working memory system can only hold a limited number of discreet items (between 5 and 9 for the loop), to increase it’s capacity we have to chunk larger amounts of information together. For example, a string of 10 one-digit numbers could be chunked into a string of five two-digit numbers.

Attention

Generally speaking, anything we’re not fully attending to will face competition for encoding. Have you ever been on a bus, daydreaming, and later be completely remember what the person in front of you looked like? When your focus is on your internal images, the input from your eyes isn’t encoded as easily (if at all). The central executive is monitoring what’s going on, of course, so if the person turned around and was incredibly beautiful, or holding a weapon, your attention would be diverted accordingly.

But the general point here is that giving something your full attention gives you a better chance of remembering it, because it will have less competition in the temporary storage areas outlined above, and is therefore more likely to be encoded and then stored in long-term memory.

References:

(1) Baddeley, A.D., & Hitch, G.J. (1974). Working memory. In G.H Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation, Vol 8. London: Academic Press.

(2) Baddeley, A.D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Science, 4, 417-423