The Rosetta Stone people are making a killing through their concept of “natural” language learning. That is, their angle is that with their product, you supposedly learn a new language in the same way you learned your first, which allegedly makes the process easier.

To accomplish this, they use pictures. So you see and hear a foreign word, and a collection of pictures, and you pick the one you think the word represents.

This makes nice, intuitive sense, although if you were skeptical you might think that this method is simply an easier way to increase the size of your product line, since pictures are universal while using words would basically mean re-writing the whole thing for each country you’re selling in. So it’d be good to see a few tests of this learning method.

You’d certainly expect pictures to be more effective, but results have been mixed. Shana K. Carpenter and Kellie M. Olson devised a few studies to tease out the answers.

A Good Old-Fashioned RCT

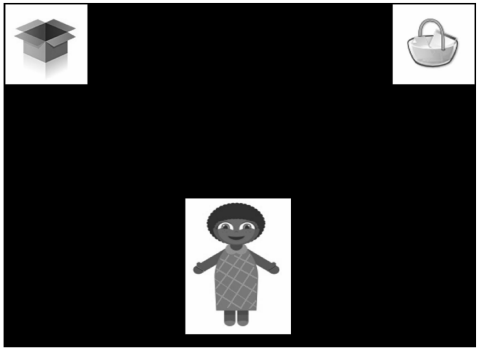

Using Swahili as the target language, they first did a standard randomised controlled trial. Half were shown a Swahili word with an English word, while the other half got a picture and the Swahili word, probably something like this:

kolb (Photo Credit: EpSos.de)

(Just to clarify, “kolb” is only the relevant part. Don’t run up to four legged animals in Kenya shouting “Here Photo Credit! Heeere Photo Credit!!”)

The results did not indicate a difference in the words learned by the participants — pictures were no more effective than words. Why could this be? One reason might be that the picture wasn’t encoded into memory very well. To test this, participants were also asked to free-recall as many pictures (or English words) from the test as they could. People who were presented images rather than words remembered significantly more items. This indicated that the lack of benefit from using pictures was not caused by insufficient encoding of the picture.

So if the pictures themselves are easier to recall than plain words, why weren’t their paired Swahili words easier to remember too? On to the second experiment…

The Multi-Media Heuristic

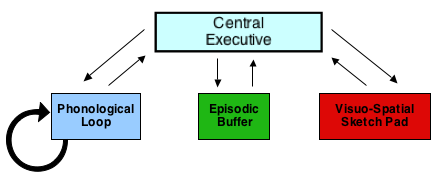

A heuristic is a basic rule of thumb that the brain uses to save time when processing. Think of it like a stereotype — to conserve the energy that would be spent taking people as they are, it’s easier to assume people possess characteristics associated to groups they belong to. There’s probably a survival thing going on here, since in life-or-death situations you need to respond quickly, so we have a built-in time saving “automatic” reasoning system.

The multimedia heuristic is the assumption people have that text combined with images is easier to remember than text alone. Seems like a reasonable rule of thumb, yet evidence doesn’t support it. Maybe when people see the picture with the foreign word, the energy-conserving multimedia heuristic kicks in and the brain allocates less resources to processing and encoding that word. Why bother with the effort? It’s got a picture with it!

So the test was repeated, but this time participants were asked, for each item, if they thought they’d remember it in five minutes. This test was repeated three times. In the first test, the pictures group was overconfident, and as before there was no difference in performance between groups. However, in the second test both groups saw a dramatic reduction in confidence (perhaps after seeing the results of the first test), and the pictures group did indeed recall more words than the words-only group! The same was found in the third test.

So it works! Perhaps by removing their overconfidence, the multimedia heuristic was assuaged and the brain provided more resources to the learning.

Don’t be overconfident!

In the third test, participants were split into two groups, each of which were tested on both picture-Swahili word and English word-Swahili word combinations. However, one group was given a little message telling them not to be too overconfident:

People are typically overconfident in how well they know something. For example, people might say that they are 50% confident that they will remember a Swahili word, but later on the test, they only remember 20% of those words. It is very important that you try to NOT be overconfident. When you see a Swahili word, try very hard to learn it as best you can. Even if it feels like the word will be easy to remember, do not assume that it will be. When you see a Swahili word with a picture, try your best to link the Swahili word to that picture. When you see a Swahili word with an English translation, try your best to link the Swahili word to that English translation.

Confidence was tested in the same way as the previous test, and indeed, the group receiving the warning reported lower confidence. Did this affect results?

Of course! People receiving the warning performed better than people who didn’t on the picture task, but not on the words task. Since overconfidence is not an issue when remembering word pairs, this both implicates the multimedia heuristic and suggests a way to improve learning of second language words — don’t be overconfident!

Maybe you can now remember the Swahili word for dog, presented earlier? It’s “kolb.” If you’re thinking “Photo Credit” I apologise profusely!

Reference:

Carpenter, S., & Olson, K. (2012). Are pictures good for learning new vocabulary in a foreign language? Only if you think they are not. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38 (1), 92-101 DOI: 10.1037/a0024828