Short Version

1) Find ways to use strengths more in your life

2) Look for supplementary knowledge on using these strengths in the domains you have chosen

3) Practice the activities that use the strengths and/or get training in them

Long Version

|

Alright. So you understand that a strength is a part of your brain that’s more efficient than other parts, like broadband is to dial-up. And you agree with me that life is easier when you stick to your strengths. Potentially, you can do anything you set your mind to, but it’s going to be a better experience if you set your mind to something that employs your strengths. Also, you’ve figured out what your strengths are through either self-reflection or questionnaires.

Now what?

The next step is to blend your strengths into your life, and get over the obstacles that come up as you do so. As I imply above, I’m assuming you’re sold on the idea of doing this; if not, re-read the links above to review the benefits, do some further reading through the books I mention or on the web, and ponder the issue further. If you’re still not convinced, then move along: there’s nothing more to see here.

If you’re still with me, let’s start with…

Strengths and Career

You probably spend between 30 and 50 hours per week working. Most visitors to Generally Thinking are from the UK and US, so you’re probably near the top end of that scale too; congratulations if you’re not. In any case, career seems like a good place to start.

You’ve got two possibilities:

1) Rearrange your present work so that it involves your strengths

2) Switch to work that does involve your strengths

Which of these you do, is up to you. I suppose it depends on how much you like what you’re doing now balanced against how much you want to fit your strengths into your career. If your current career doesn’t appear to make use of your identified strengths, don’t immediately conclude you’re miscast, because using option 1 you might later find yourself a good fit.

Rearrange

Here you have to discover what strengths you are currently using, then see if you can add the other ones into your role. Your position might employ one or two of your strengths really well, then it’s a matter of finding ways to add the others in. If you can’t find ways to add any of your strengths in, you’re currently going against the grain. You should consider what’s keeping you doing this, and consider Option 2. If your current role is temporary or a stepping-stone job, you’ll still enjoy it more if you can rearrange the way you do it around your strengths.

|

The various books on strengths offer basic examples on how to rearrange, such as a cashier with the strength of social intelligence, who started engaging customers more in conversation at the checkout. If I described how to use every strength in every possible role, I’d be about 80 when I finished this article, so you’ll have to get a bit creative. But since Gallup discovered that successful people find ways to do this, it’s potentially worth the effort.

The other day I was reading interviews with two rock-band front-men, Rivers Cuomo of Weezer, and Tim Wheeler of Ash. Here’s an example of two people in the same role, unconsciously fitting their strengths into it. Rivers is shy, introspective, and did an English Literature course at Harvard. He’d probably show up strengths like intellection, analyse or learner. Tim seems more charismatic and confident, he parties a lot and might have the strengths of Woo and Positivity. Both are the primary songwriters for their respective bands, so their biggest strength will surely be Arranger, or the VIA strength Creativity.

But they seem to lever their other apparent strengths into the mix too: Rivers analysed songs by the Beatles, Nirvana and other bands, and created a file called “The Encyclopaedia of Pop”. He then extrapolated a songwriting framework from this analysis, which he uses to write his songs. Tim writes upbeat and positive songs, drawing inspiration from things like sunshine and having a good time. Both of them are very successful, with multiple platinum selling albums.

Switch

Option 2 is easier from the point of view of fitting your strengths in, but harder in that you’re making a big change, which most people don’t find easy. If it’s time to make a change, then looking at your strengths, it should be fairly easy to draft up ideas for roles which involve them.

|

For example, looking at my own readout in the last article, my strengths were based around learning, curiosity, critical thinking, and forward thinking. So I’m suited perhaps for something like research, where all of these come into play, and also something like writing or blogging, so I can make extra pocket money by writing about what I learn, and of course learn more about it in the process. Hmm, what a coincidence, this happens to be the direction I’m heading in. Don’t say I don’t practice what I preach!

What strengths can’t tell you is the field you could go into – Gallup’s research did not indicate a relationship between fields and strengths. For example, you could play the role ‘journalist’ in any number of fields: science, politics, celebrity gossip, and so on. Strengths offer guidance on the role – not the field.

Managing Expectations

Remember, your aim is to look for ways to make more use of your natural and spontaneous ways of responding to the world. You’re not searching for something that you’re already a master at! Excellence will come later. Faster, but still later.

This is an important point to remember, which Marcus Buckingham makes clear in Now, Discover Your Strengths. What if you arrange your whole life around your strengths, and then still don’t find the good life? You’ve already given it your best shot, and with your strengths, no less! Buckingham says “When the cause of failure seems to have nothing to do with who we really are, we can accept it.” I’ve already drilled into you that your strengths are an enduring part of you, so what kind of torment would partner this kind of failure? Buckingham suggests the fear of this could put you off trying.

|

If you never give it your best shot, you’ve always got an excuse, haven’t you? Like the would-be suitor in a nightclub who acts like a little strange when talking to the attractive girl; a little bit too cocky, a little bit exaggerated. If the girl turns him down, it’s not him she’s rejecting, it’s the act. His ego and pride are protected, safe and sound. But of course what he gains in ego-protection he loses in effectiveness.

I think the parallels here are similar. To me, it seems more sensible to find ways of dealing with a wounded ego than to not bother at all. There’s all kinds of ways out there that offer to do that; meditation, cognitive behavioural therapy, progressive exposure, and so on.

To bring up a final question for this section: is feeling a certain way really a good reason not to do something? I had this idea when thinking about Steve Olson’s article on procrastination. I’m not talking about safety and survival instincts; if you feel a dark alley is unsafe, that definitely is a good reason not to walk down it. I mean more benign decisions. There’s a lot going on in this culture – more people around than our brains are really designed to cope with, then there’s media, bills, careers; a whole cacophony of expectations placed on us. How would you know whether a certain feeling you have should be trusted, like you would with the dark alley, or when it comes from something that you’ve arbitrarily integrated from the outside, with no particular relevance to you personally? I don’t know the answer to this, so please let me know if you do.

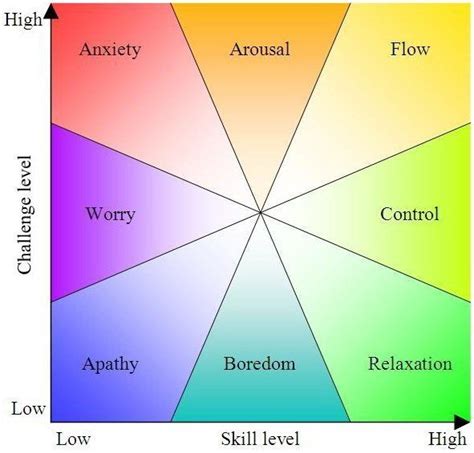

Add skills and knowledge

Using the strengths more in your life is a road to happiness, more engagement, and all sorts of other benefits. It’s also a road to greater performance – a better chance of reaching excellence in your chosen field. But as we’ve just seen, you still need to hone your strengths further, by deliberately practising them, and also by adding in skills and knowledge.

|

The reason for this is summed up in Gallup’s definition of a strength – to achieve “consistent, near perfect performance”. In fact, Gallup define a strength as a strength only after the skills and knowledge have been appropriated. They call them ‘talents’ prior to this; I’ve just used the term strength for convenience, and to compare models. To get this level of performance, you may need to focus your efforts on one or more strengths, like the rockstars I mentioned above, who apparently focus on creativity, and use the other strengths to support this effort. This was an easy choice for me too, as three of my top five strengths are mental/reflective, so it was obvious that this is the place to focus.

The skills and knowledge you pick up will be experiential as well as deliberately researched or taught. Some things you simply can’t get except through hands on practice, other things you can get from a book or trainer. Our rockstars above may have had knowledge training in the form of music theory, skills training through tuition and practising scales, but their unique style of guitar playing and song-writing, that can only come through hands on practice – allowing their brains and nervous systems to end up with pathways and connections, causing them to respond to a guitar and to music the way they do. There’s really no way of getting around this.

This just about wraps up this series on strengths, barring a couple of loose-ends to tie up (managing weaknesses, for one). Thanks for reading, hope it’s been useful!

Recommended Reading:

- StrengthsFinder 2.0: A New and Upgraded Edition of the Online Test from Gallup’s Now, Discover Your Strengths

- Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification

- Average to A+: Realising Strengths in Yourself and Others

[Lego Strength image by Coldpants]