As many of you know, I’m in the process of writing a book: a psychology study guide to be precise. One of the things it will cover is time management, planning, productivity; that sort of thing. While researching this chapter (the last one to do I might add), I remembered an interesting study that Tim Ferriss mentioned on his site. It found that people who were distracted during an IQ test by email and ringing phones actually did worse than people who were high on marijuana. That’s just the sort of quirky study I’d love to cite. It’s interesting, it would stick out in peoples’ minds.

In Tim’s words:

“In 2005, a psychiatrist at King’s College in London administered IQ tests to three groups: the first did nothing but perform the IQ test, the second was distracted by e-mail and ringing phones, and the third was stoned on marijuana. Not surprisingly, the first group did better than the other two by an average of 10 points. The e-mailers, on the other hands, did worse than the stoners by an average of 6 points.”

I wanted to find the original study for my book. With the help of Matt Fox of Persuasion Theory fame, I tracked down a Beyond the Biz article entitled “Study offers dope on e-mail madness” (good title; not as good as mine), which had more details of the study. Some highlights:

“E-MAIL HAS A MORE DETRIMENTAL EFFECT on British workers’ IQs than smoking marijuana, according to a Hewlett-Packard study conducted by TNS Research. Dr. Glenn Wilson, a psychiatrist at King’s College at London University, monitored worker IQ throughout the day in 80 clinical trials. Wilson said the IQ of workers who tried to juggle e-mail messages and other work fell by 10 points-more than double the four-point fall seen after smoking pot, and about equal to missing a full night’s sleep.”

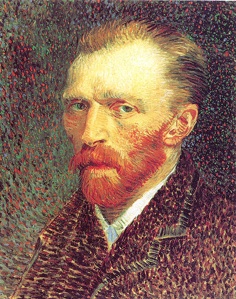

We have a name! And it’s the well-known Dr Glenn Wilson, no less. And he monitored IQ throughout the day? In 80 trials? Wow, must be a solid finding! The article continues:

“He added the IQ drop was more significant in men in the study, which was conducted with 1,100 people. Wilson advocates companies helping employees solve the problem. “Companies should encourage a more balanced and appropriate way of working,” he said.”

OK so now we’re talking about ‘the’ study with 1,100 people. Is that in each of the 80 trials? That would make 88,000 participants. That’s a lot of pot! Either something’s amiss here or Dr Wilson has his ethics committee wrapped around his little finger! So maybe those 1,100 people are spread across the 80 trials. That would make an average of 13.75 participants per trial. I’m not sure which is most unlikely – a psychiatrist doing 80 trials with less than 5 participants per group, or 29,333 people getting stoned in the name of science.

This is not looking altogether kosher.

In a section of his site called “The Truth,” Tim Ferriss cites a New York Magazine article on Dec 4th 2006, called “Can’t Get No Satisfaction.” For your convenience, here is a link directly to the page of the magazine in question. For your greater convenience, here is a quote of the relevant section:

“In 2005, a psychiatrist at King’s College London did a study in which one group was asked to take an IQ test while doing nothing, and a second group to take an IQ test while distracted by e-mails and ringing telephones. The uninterrupted group did better by an average of ten points, which wasn’t much of a surprise. What was a surprise is that the e-mailers also did worse, by an average of six points, than a group in a similar study that had been tested while stoned.”

As you can see, New York Magazine clearly states that there were TWO groups in the study. The marijuana group data was from another study. Comparing data from one study to data from a ‘similar’ study is not something you should do without firm justification. They didn’t even give references.

But whatever, even though the marijuana aspect is pretty central to these articles, I’m more interested in the effects of distracting emails so I can write about it in my book. So I did some further digging to find the original study.

Conveniently, Glenn Wilson has a report on his site here (it’s the ‘infomania’ link at the bottom). This cleared everything up.

Wilson was commissioned by Porter-Novelli to supervise an in-house experiment, which would accompany a survey of 1,000 people. Wilson had nothing to do with the survey, and just helped out with the experimental side of things.

His study tested 8 employees in two conditions – a ‘quiet’ condition and a ‘distracting’ condition (mobile phones ringing, emails arriving; usual office stuff). He measured IQ with a matrices-type test (which I’m not familiar with), as well as physiological measurements. He did find that distraction reduced IQ performance and increased stress, but 8 participants? That’s a pilot at best. Hardly newsworthy.

But no blame on poor Wilson here, he just did the job he was asked to do. It’s in the reporting of the study where things went a little bit silly.

Somewhere along the line, “8 participants” become “80 clinical trials”. That is absolutely laughable. The 1,100 participants obviously came from the 1,000 participant survey that came up. But it is shocking how people will literally lie like this.

Wilson leaves a note at the end of his report:

“This study was widely misrepresented in the media, with the number of participants for the two aspects of the report being confused and the impression given that it was a published report (the only publication was a press release from Porter-Novelli). Comparisons were made with the effects of marijuana and sleep loss based on previously published studies not conducted by me. The legitimacy of these comparisons is doubtful because the infomania effect is almost certainly one of temporary distraction, whereas sleep loss and marijuana effects on IQ might conceivably be more fundamental, even permanent.”

And later said on the matter:

This “infomania study” has been the bane of my life. I was hired by H-P for one day to advise on a PR project and had no anticipation of the extent to which it (and my responsibility for it) would get over-hyped in the media. ??There were two parts to their “research” (1) a Gallup-type survey of around 1000 people who admitted mis-using their technology in various ways (e.g. answering e-mails and phone calls while in meetings with other people), and (2) a small in-house experiment with 8 subjects (within-S design) showing that their problem solving ability (on matrices type problems) was seriously impaired by incoming e-mails (flashing on their computer screen) and their own mobile phone ringing intermittently (both of which they were instructed to ignore) by comparison with a quiet control condition. This, as you say, is a temporary distraction effect – not a permanent loss of IQ. The equivalences with smoking pot and losing sleep were made by others, against my counsel, and 8 Ss somehow became “80 clinical trials”.

Since then, I’ve been asked these same questions about 20 times per day and it is driving me bonkers.

You’ve gotta feel for the guy.

So even though I’m a little late to the party I thought this was worth mentioning, just to highlight that you cannot trust something just because it has been published – even in so-called ‘reputable’ places.

Remember, this was an in-house study with 8 participants which had *nothing to do with marijuana whatsoever*. And look what happened:

Any my personal favourite:

- Email destroys the mind faster than marijuana – study (The Register)

DESTROYS the mind! Are you kidding me?!

All these articles mention the marijuana link too.

So whose fault is this? I don’t know who started it. I can’t be bothered to check. It wasn’t Tim Ferriss. But everyone is guilty of not checking their sources. This time the only victims were Dr Glenn Wilson’s inbox and a few concerned citizens, but you can imagine how the same process on more serious topics could be quite destructive.

It would be nice if the sources above updated or removed the articles in light of the fact that they are, well, a load of bullshit. Out of curiosity over what would happen, I sent the following email to most of the above sources:

To whom it may concern,

I’m writing with regards to your article:

XXXXXX

Which discusses the effects of marijuana on IQ. I thought I would bring to your attention the fact that your article is incorrect. The study in question did not actually look into the effects of marijuana at all, although this is certainly an honest mistake, as many news outlets have made the same error.

The true study was:

* A small test involving 8 participants

* Looking at distractions of email/phone against quiet conditions

* Not connected with the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings, except for the fact that the person hired to supervise the study, Dr Glenn Wilson, is a member of that faculty

Further information is available here:

http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/002493.html

In the interests of accurate news reporting I am bringing this matter to your attention so that you can make the necessary alterations to your article.

With kind regards,

Warren Davies

As you can see, I sound very polite and formal. I thought I would be taken more seriously that way, as opposed to an informal “Hey dude! FYI….” . Let’s see if anyone will agree to change their article to reflect the truth. Tim Ferriss is difficult to contact by definition, but I’ve sent him a message on twitter just in case.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to get to work on that book chapter I was talking about. Right after I check my email and finish this bong, that is.