This is the practical part of this series on happiness. It’s quite long, and not necessary to read through it all. The only essential part is “The Happiness Formula” – after that feel free to bookmark or skim, if you prefer not to read the whole thing.

This article is different to the other “how to be happier” articles I found on the internet. The other stuff seemed to be more inspirational and uplifting rather than practical. I found advice like ‘smile more’, ‘be myself’, and ‘get a cat’. This article differs because it’s not just 10 pieces of advice I made up as I went along. It’s a review of different methods that have been tested scientifically. They’re tested in the same way drugs are: measure happiness before, give the intervention, and measure happiness after.

You’re not supposed to do everything at once! This is just a resource of ideas for you to try. If you want to be thorough, you can measure your happiness with a scale, try something out for a week or two, then measure again. You can find many scales here (Authentic Happiness Inventory is probably the best one to use; the site is free but requires registration).

The Happiness Formula

What your instincts tell you about how to be happier is probably wrong. Most people try to change their happiness by changing their circumstances. The logic is, by changing their life situation to one they are happier with – more money, better house, different gender, whatever – they’ll become happier because they like the new situation more.

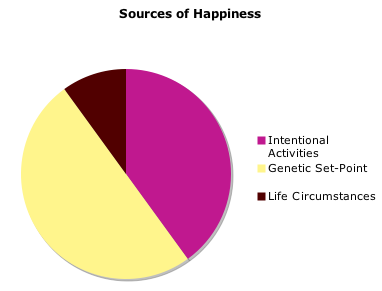

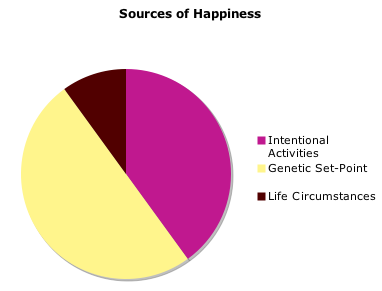

This idea is basically misguided, although true to an extent. The happiness you experience comes from three sources; your genetics, your life circumstances, and your intentional activities, split like this:

So the ‘happiness formula’ is this:

Happiness = Genetic Set Point + Life Circumstances + Intentional Activities

We’re stuck with our own set of genes for life, so no luck there. Our life circumstances are only slightly relevant. This includes where you live, your gender, health, money, marital status, and so on. We can change all of these, but they only take up 10% of the happiness pie. Ten percent is not insignificant, but the most logical place to take action is ‘intentional activities’ – anything you deliberately think or do. (1)

This might seem backwards, but it makes sense when you add in the concept of adaptation – many things give us a boost in happiness, but we adapt to them over time, and the happiness wears off. Circumstances are more long-standing. Intentional activities are short-term: no time to adapt.

So take marriage. Marriage is long-term, and seems to make most people happier for a few years, before they adapt to it. But expressing gratitude to each other, having those awful picnic things where you feed each other food (yuck!), talking about all the other disgustingly romantic things you did together; these things boost happiness, but as they are episodic there’s no adaptation to them. You just have to keep doing different activities.

The following are ideas all fit into the intentional activities slice of the pie.

1) Expand your Social Network

Social relationships are a bit of an exception to the above rule, because they’re something we don’t adapt to. If you have close relationships in your life, you’ve got a regular source of happiness (unless they are bad relationships, of course).

It’s possible to live alone in this world – if you could get a job with no human contact, and afford a house and food you’d be able to survive. But ten thousand years or so ago, you’d be dead without relationships. No one in your tribe would help you out and you’d have no allies if some cave-criminal decided to steal your lunch. For that reason, we have a brain system that ‘rewards’ us with happiness if we make a new friend or even just have an interesting conversation with someone.

Aha, you might say, I know a person who really likes their own company more than other people! Yes there are some people like that, but a group of mischievous researchers once took a group of introverted people, and forced them to talk and relate to people, and even they enjoyed it. (2)

If you’re on a quest for success, like getting a load of money or building a strong business, some people will tell you that’s a bad idea. Don’t put all your time into it at the expense of your friends and family, they say. It’s not what’s really important, etc.

But they are actually right. You’ll probably still want your success, but it would be useful to remember that you will adapt to success, you won’t adapt to relationships, and that wanting something and liking it are different things.

How to get more social ties into your life is a whole other series of articles. Obvious ideas are find work that involves human contact or working in a team, join clubs, learn social skills, and generally just get out more.

2) Change your Thinking

Our actions can be broken down into three things – thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. Any one of these things will affect the other two. If you feel happy (emotion), you’ll tend to have happy thoughts too. If you furrow your brow and shout aggressively (behaviour), you’ll start to feel angry (emotion). And if you think that your life is terrible and there’s no way out for you, soon enough you’ll start feeling sadness and despair. Feeling sad will make you take the actions of a sad person, which will make you think more sad thoughts, and downward spirals like this can sometimes lead to depression.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a form of psychotherapy intended to break people out of downward spirals of this kind. The main method used is to intervene at the ‘thought’ stage of the spiral, by teaching people how to logically challenge the thoughts that are leading to the negative feelings and behaviours. Negative thoughts have predictable structures, which have been identified and labelled. There are specific challenges for the different types of thought, clients are trained in them, and use them whenever such thoughts occur.

So for example, as soon as the client thinks “I always do stupid things”, he recognises this as an over generalisation and challenges it with counter-questions like “is there a time I didn’t do a stupid thing?” His questions expose the logical flaws and weaken the negative feedback loop. There are also sometimes ‘homework’ assignments, addressing the ‘behaviour’ part of the spiral, such as exposure to gradually more anxiety producing situations.

CBT doesn’t necessarily prevent the natural occurrences of negative thoughts, but can stop them turning into huge downward spirals, and also interrupts current spirals that are already spiralling. This doesn’t mean that it will only work for people who are unhappy to start with. Everyone experiences setbacks at various times, and this is where it can be useful to have a better way of dealing with them. It’s a tool you can use to take a more optimistic outlook on something.

A good book with exercises based on CBT is Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism. Most of the other books and websites I found on CBT were focused on treating specific problems like anxiety and depression. These are good for learning the techniques and methods of CBT, which you can then apply to your thoughts in general. Of course, if you believe you suffer from a serious condition, you should seek the advice of an expert rather than try to self-medicate.

3) Meditation

There’s a mystical image surrounding meditation. When I talked with people about it, I got the impression it’s seen as, new-agey, and a bit ‘out-there’, perhaps involving people in orange robes chanting “oohhmm.” In reality, it’s just a practical exercise for training the mind, just like you train the body. There are many different types, but the one I’m talking about here is called mindfulness meditation, and this itself is taught in various ways and known by different names. Vipassana is one form you might have heard of (as practiced by celebrities such as Madonna and Rivers Cuomo).

Mindfulness meditation involves deliberately directing your attention to something, typically your breathing or an object, and not allowing any thoughts to enter your head as you do so. As soon as your mind wanders, you just become aware of it, acknowledge it, and bring your attention back to the breathing. You do this for 20 minutes a day or so, building up the time you do it for. Very simple, but not very easy.

So it’s about learning to control your awareness so that you can place it wherever you want, which will usually be wherever you are at that particular time. You know all this “be in the moment!” spiel that you seem to hear everywhere these days? That might well be good advice, but without telling you how to control your attention, it’s a bit like saying “be physically strong!” without giving a weight-lifting program. Mindfulness is one way of controlling your attention.

And it also makes you happier. In one study, participants were given an 8-week program in mindfulness meditation. After the program, EEG scans measured increased activation in the left side of the anterior cortical area of the brain, the area associated with positive emotions. Additionally, the participants were given the influenza vaccination at the end of the program, and the meditators actually had a stronger immune response to it than the control group. (3)

Jon Kabat-Zinn’s book Wherever You Go, There You Are is a very good introduction to mindfulness, and you can also find a video of a speech he gave here, where he describes what mindfulness is and how to do it. (the instructions start at around 24mins). Finally, there’s a very thorough and free mindfulness resource at http://www.vipassanadhura.com/howto.htm.

Beyond this, there are also courses around the world teaching mindfulness meditation. Many of the courses are free, like the Vipassana ones, which basically involve going to a retreat for 10 days and meditating for 18 hours a day. Sounds very intense. So investigate this further if you want more instruction.

4) Positive Reminiscence

In a way, this one is the opposite of the meditation I just mentioned. In meditation, you generally move your attention away from thoughts, and certainly don’t encourage them. In positive reminiscence, you deliberately think about your various happy memories. When people were asked to spend 15 minutes a day for 4 weeks reminiscing on happy memories, they ended up happier than groups asked to think about neutral or sad memories. (4)

It’s important that you’re just reminiscing, and not analysing. In another study participants were asked to systematically analyse their happy memories – this actually caused a reduction in happiness. Any skilled meditator would probably predict this, as a big aspect of meditation is learning to think non-analytically. It seems that analytical thinking, and creating judgements around thinking, is not useful when happiness if the goal.

So as long as you’re just reminiscing, and not evaluating the past, you’ll be OK. Remember; 15 minutes a day. Don’t sit there daydreaming and wasting your time away.

5) Pursuing Goals

Some scientists believe that happiness is a system built into our brains to help us reach goals. When we progress to our goals, we become happier, when we’re lagging behind, we get less happy, even anxious. That’s partly why humans like challenges. Well, most of us do; some prefer to simply sit down, eat and watch Prison Break. But for the rest of us, making progress towards a goal will bring happiness along with it.

A study in the early 1990s found that the more committed to a goal you are, and the more attainable it seems, the happier you are when you reach it. Another in 2002 found that if you train people in how to set and reach goals, they experience more positive emotions, vitality, and wellbeing. So it seems that if you are committed and strategic about it, your goals will work better for you – probably because you have more chance of reaching them! (5)(6)

But remember what I said earlier about adaptation – the happiness from a goal being reached won’t necessarily last, so setting one like earning more money is a lot like running on a treadmill – you’ll break a sweat but you’re not going to get anyway. You’re like the donkey trying to reach the carrot.

There are resources to help you set and follow goals all over the net and in self-help books, so I won’t go into it here.

6) Writing

When I say ‘writing’ I’m referring specifically to things like journals and diaries. Although writing in the ‘Dear Diary’ sense is stereotyped as ‘for girls’, historically it’s been popular with both genders. You can buy the The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin from Amazon very cheap. I did. It’s quite good, he was a very industrious and motivated chap, which I suppose you’d need to be if you wanted to help found a country.

There are two types of writing you can do. I’ll call these disclosive writing, which refers to writing about negative or distressing events, and positive writing, which is writing about positive things you want to happen.

Disclosive Writing

A massive amount of research has been done on this – a review in 2005 analysed 146 experiments, and found it to be effective (7). Essentially, you write about negative or traumatic events, and the structured nature of written language causes you to create a narrative out of the event. When systematically structured like this, the event is more easily processed by your mind, and you get a better sense of understanding and closure. The more ‘insight’ words (eg, understand, realise) and ‘causal’ words (eg, because, reason) that end up in the narrative, the stronger the effect is. This shows that the benefits come when writing is used to help make sense of bad events.

The book Writing to Heal has exercises on how to do this. It’s written by James Pennebaker, one of the major researchers in the area.

Positive Writing

With positive writing, you don’t write about happy memories. Breaking down a negative event can help remove negative feelings, but as we’ve already seen, you don’t want to be analysing or evaluating positive events – in your head or on paper. Why would you? If you want the feeling that they create, you can elicit that by reminiscing – there’s no need to structure a narrative around it.

Instead, with positive writing you write about what is termed your ‘best possible self’. This is quite a self-helpey exercise, but there is research behind it. You imagine yourself as you’d like to be, on paper. It’s as simple as that, just write out in detail what your future is like after you’ve met all your life goals realised all your dreams, and so on. I’m not sure why this works, maybe it helps you to stay optimistic, or maybe it has a similar function as creating a goal, giving you something to aim for. Whatever the mechanism is, it does seem to work.(8)

7) Expressing Gratitude

Gratitude, if you didn’t know, is a sense of thankfulness and appreciation aimed towards something specific. It’s a positive emotion in itself, so it’s not too much of a surprise that feeling grateful more often will be good for your happiness; but there’s more to it than that.

Gratitude can be used as a coping strategy, to reframe a negative experience in a positive way. You broke your leg, but you’re grateful you didn’t break both. When directed at experiences in the past, it serves to help savour them.

Remember, we adapt to many events that make us happy, and they lose their magic after a time. If you get a new car, it makes you happy for a while because you can compare ‘new car’ with ‘old car’. A year down the line, you’re comparing ‘new car’ with ‘new car’ – you’re used to it. With gratitude, you are countering the effects of adaptation to an extent, by manually overriding what is being compared.

A popular gratitude exercise is called ‘three good things’. It’s simple; every night you write down three good things that happened to you that day, and why they happened. In one study, happiness gradually and consistently increased over six months of doing this (9). In another ten-week trial, participants ended up happier, in better physical health, and strangely, were spending more time exercising. (10)

This is a simple exercise, and doesn’t take up much time, so it’s certainly worth a try. But be aware that the results are modest initially, and it takes some months for the effects to build up.

8 ) The Gratitude Letter

If you scanned this page to look at the headers, you’d probably find some to your liking, and others you didn’t like the look of. The gratitude letter is one that is seriously not to my own liking! Maybe it’s a side effect of being British, but the thought of doing this makes me cringe greatly. However, it does actually work, and some people really like it, so if it sounds good to you then go for it. Here’s how to do it:

You think of a person who really helped you out, that you never properly thanked. You write a letter to them, expressing your gratitude for all the lovely things they did for you. But you don’t post this letter off. Oh no. That would be too easy. What you actually do is go visit them in person, and read it out aloud to them. Then what happens, apparently, is you both get all emotional, and you might even both cry. But after this, your happiness gets a very large spike, which lasts a few weeks as you bask in the afterglow of appreciation. Then it gradually wears off, and you go back to normal. (8)

9) Discover and Use Your Strengths

People always tell you to ‘stick to your strengths’, and it’s actually pretty good advice. The more you work your strengths into your daily routine, the happier you get happier. I know because I did an experiment on this for my dissertation. But how do you know what your strengths are? In 2004, after a huge amount of research, a tome by the name of Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification was published. This volume classifies 24 character strengths, some of which you use a lot, while others you use very little.

There’s a test you can take at authentichappiness.com, which will place the 24 strengths in rank order for you, so you’ll find which are your real strengths and which are more like weaknesses. It does take around 45 minutes though. After the test you’ll get some details on your top five strengths, which they call your signature strengths. Research has shown that if you deliberately make use of these strengths on a daily basis, you get happier. And it seems that the longer you do it for, the happier you get, although no research has been done past the 6 month mark. (8)

The idea is to integrate the signature strengths into your daily lives. Find hobbies and interests that use them, rethink how you go about your work to use them more, and so on. There are some other ideas here (Click the strengths vs weaknesses link – it’s a Word document, scroll down to the appendix).

10) Random Acts of Kindness

Kindness, generosity, nurturance, altruism, or whatever you want to call it, is the cornerstone of most religious and ethical systems. For some reason, performing acts of kindness makes the giver as well as the receiver happier. Maybe it increases the sense of interdependence in the community, which is good for everyone. Maybe it’s because of the reciprocity principle – if you receive something, you are motivated to give back. This is why restaurants give you the mint instead of leaving it in a bowl – it makes people tip more!

Again though, it works, whatever the reasons. College students who were asked to perform five acts of kindness, one a week for six weeks were significantly happier at the end of it. In another study, people were either asked to perform the same act of kindness, or varied acts of kindness for ten weeks. Interestingly the group performing the same act did not see an increase in happiness. Maybe it was the effect of adaptation, maybe just boredom; who knows? But it seems you must be a bit creative about your kindness for it to work for yourself. (10) (11)

Two Final Thoughts…

Mileage May Vary

Well done if you’ve made it this far. There’s a lot to choose from, and now you might be wondering, what will work for me? In the experiments that these techniques were based on, there will undoubtedly be people for whom it didn’t work, and psychologists haven’t figured out yet which interventions are best for which people. Personally, I don’t like the idea of the gratitude letter, and writing about my best possible self. But other people will love them and benefit from them – there’s proof of this. Then again, maybe I would randomly find I love positive writing. Who knows? The point is, some trial and error may be required.

Also, remember to give these techniques at least a full week, preferably a few, before you evaluate how good they are. And give them a fair try – you need to do them regularly and habitually for them to work in the longer-term. If you just want a bit of short-term happiness, go get a massage or something.

Be Realistic

The biggest block to happiness is not in the external world, but in our own psychology. The systems of happiness, pleasure and desire that we all possess are not there for our enjoyment; they are there to help the organism known as ‘the human’ function effectively. The body does not care if you are happy. If it can trick you into pursuing things that you think will make you happy, but actually are just helping you survive, then it will.

If you become as materialistic as possible and do nothing but work and sleep, you’ll get pretty rich. With money comes security, you can buy a big house, good food, and enjoy high status. You can even get a gold digging wife or husband, and have some kids. Your body doesn’t care if you are unhappy all your life, as long as you survive and reproduce.

That’s why you have to be a bit smarter when it comes to happiness. You have to know the system to work it. The above methods are the result of work people have done to that end. If any of them look appealing to you and you want to give them a try, by all means do it. It will probably work.

But remember one thing; true and complete happiness is impossible to achieve. It’s not in the nature of happiness for it to be fully obtainable, nor is it possible for happiness to evolve so that it is fully obtainable. So don’t make happiness too big of a deal. It’s only one part of life. You’re not supposed to be happy all the time. There are other things in your life that you need to do, that require other emotional and mental states.

Besides, if you focus on it too much, you’re not likely to get it. It’s often more effective to find engagement elsewhere, and let it come to you.

Don’t think that you need some incredible life to be happy. Don’t think you need some spectacular level of happiness to be normal. We can use science to break happiness down into little pieces, and do experiments to see how to increase it, but experiments can’t tell you how happy you should be. Each individual person has to answer that themselves, and every answer will be different.

Of course, if you don’t answer that question yourself, an answer will be provided for you. We’re inherent comparers, us humans. We’re always looking out for what other people have got. In a world with things like the internet, television and magazines, we’re constantly exposed to the most attractive, most talented, most charismatic of about 6 billion people: which can sometimes make us want too much.

I found an interesting quote:

“The world is full of people looking for spectacular happiness while they snub contentment”

It doesn’t say who said it, but I think it’s worth keeping in mind.

References

In the first comment…