Strengths-based approaches to work and life are popular these days; particularly in how personal strengths can improve leadership, as better leaders mean better experiences for employees, more productivity, and more money (or other bottom line). But a key question is, do leadership strengths exist? Are there strengths that all leaders share? If so, what are they? And if not, how can the current perspectives on strengths create better leaders?

What makes a good leader?

“Good Leader” seems to be a fluid concept, depending very much on the context. Strengths-based approaches to leadership argue that good leadership isn’t a matter of having a specific set of “leadership strengths,” but rather, it’s a matter of leveraging the strengths a leader already has in a way that gets the job done. This isn’t to say that certain skills and abilities aren’t required by most, if not all leaders; it’s just that there isn’t one particular ‘mould’ that a person has to fit into to be a leader – they come in all shapes and sizes.

There are two major models of strengths – StrengthsFinder and Values in Action. If you’re a follower of the ‘strengths movement’, you’ll be familiar with at least one, if not both of these; if not, you can find a comparison here: Values in Action Vs StrengthsFinder.

The StrengthsFinder Perspective

Gallup’s work on leadership strengths is found in the book Strengths-Based Leadership. They conducted thousands of interviews to create the Strengths Finder model, and they didn’t find any one strength that all leaders shared. But, they did find that the most effective leaders invested in their own strengths – and the strengths of their team.

Why aren’t certain strengths more common among good leaders? It could be because of leadership styles. Research identified four common styles: executing, influencing, relationship building, and strategic thinking. The 34 Gallup strengths are linked up to these categories, and the style of leadership you’re likely to use is related to which of these categories your personal strengths are in. This is why good leadership is more a matter of using your own strengths, as opposed to fitting the mould of a mentor, or stereotype.

But this line isn’t so concretely drawn, as they found a few more interesting things:

- Followers look for trust, compassion, stability and hope from a leader

- Leaders understand their followers’ needs

- Leaders create teams based on people who have strengths that compliment their own, as I briefly mentioned in strengths and weaknesses.

So while no particular StrengthFinder strength is necessary, leaders do need to know their own strengths and weaknesses well enough to form a team around them, and they also need the necessary perceptiveness to understand their team members’ needs.

The Values in Action Perspective

The VIA model views the ability to lead as a strength in itself. They measure leadership one-dimensionally, rather than scoring you on different theoretical aspects of leadership. And it’s done through self-report, so your leadership strength is reflected by your answers to questions about how often you lead, your opinion of yourself as a leader, and your opinion of your friends’ opinions of yourself as a leader, and so on.

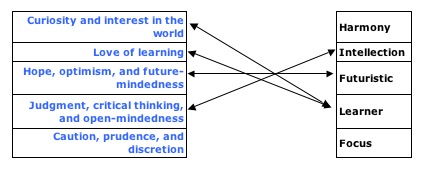

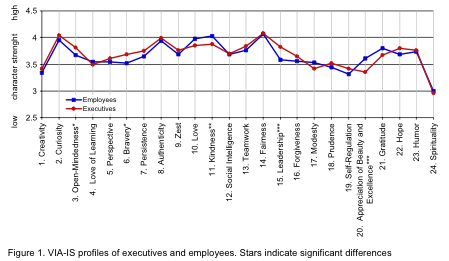

This is a bit open to error, just as all self-report measurements are, but based on the Gallup findings it might be the most accurate way to do it. I only found one study looking at the VIA strengths of leaders, which compared CEOs with their employees. You can get a pdf from the University of Zurich’s website. The results are below, hopefully they won’t mind me copying this graph here:

As you can see, there’s very little difference between the strengths of CEOs and employees, which the Gallup research would predict. There were a few differences though – CEOs were higher in ‘open-mindedness’, ‘bravery’, and ‘leadership’, but lower in ‘kindness’ and ‘appreciation of beauty and excellence’.

(You may notice other differences on the graph, but these weren’t ‘statistically significant’, which is jargon basically meaning the scores are too close together to know if the slight difference was a fluke finding or not).

Although these differences seem to go against the StrengthsFinder results, they don’t really. As I know Gallup reached their conclusions through interviews, so it would have been qualitative research and open-ended questions. So they wouldn’t be able to pick up subtle differences like the VIA questionnaire would. Also, this study only looked at one type of leader – CEOs, a very distinctive type, which might attract people with a particular leadership style.

With the graph showing such similarities between CEOs and employees, the general idea that there’s no specific leadership strengths holds up here too – at least based on this one study, and exluding ‘leadership’ itself obviously.

So what makes a good leader, from a strengths perspective?

- You don’t need any leadership strengths per se, but you need to know and invest in the strengths you do have (which you might do through self-reflection or questionnaires).

- You must know your weaknesses, and shape your team to compliment them.

- Finally, be perceptive enough to understand the needs of your team. Individual needs, you’ll have to work out yourself, but generally speaking people tend to look to leaders for trust, compassion, stability and hope.

Although this field is quite well researched, it’s not without critics. So if you’re interested, you should look into the field further and see if you think it’s worth trying out. The book Strengths-Based Leadership would be a good place to start, and there are also some good blogs that deal with strengths and leadership, like Clifton Strengths Blogger, and The Practice of Leadership.

Recommended Reading:

- StrengthsFinder 2.0: A New and Upgraded Edition of the Online Test from Gallup’s Now, Discover Your Strengths

- Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification

- Average to A+: Realising Strengths in Yourself and Others