Beyond Money: Towards an economy of well-being is a 2004 paper by Ed Diener and Martin Seligman. Here are the key points.

Overview

Economic indicators like GDP and the employment rate are dominant when it comes to making policy decisions. Such statistics are important and relevant, especially when it comes to the fulfilment of basic needs – wealthier countries are more likely to provide food, shelter, and security to their citizens. However, economic indicators have a number of of shortfalls. Not only do they fail to provide the full picture of well-being in a society, but in some respects they may actually be misleading in that regard.

Economic indicators should be balanced out with a wider range of statistics that give a clearer picture of how well a society is flourishing. These include well-being and mental health measurements, social capital, and human rights.

Not only will this give governments a better idea of how to create effective policies, but improvements in these non-economic indicators will likely lead to improved economic performance in any case.

Details

A number of countries have developed their own national well-being index. The EU runs regular surveys measuring well-being, the UK introduced well-being measures under David Cameron’s government, and Bhutan was a trail-blazer in this regard.

A lot of this has to do with psychologists putting a lot more effort into studying happiness around the turn of the century. A paper in 2004 by Ed Diener and Martin Seligman entitled “Beyond Money: Towards an Economy of Well-Being” summed up the research that was available at that time, making a case for such well-being indices.

Here’s an overview of the key points in the paper.

Key argument

Economic measures give an incomplete and sometimes inaccurate indication of how well a society is flourishing. Policy makers should make the development of valid well-being measurements a priority, and use the data to inform policy.

What is well-being?

Psychologists define well-being as people’s “positive evaluations of their lives”, taking everything into account. These evaluations are affected by things like the amount of positive emotion people experience, how engaged they are in what they regularly do, how satisfied they are with their life situation, and how much meaning they get from their lives.

More info on how happiness is measured here.

What’s wrong with economic indicators then?

They have their uses, of course, but they are perhaps over-used. The news tells you how the economy is doing every day. How often do they tell us how satisfied, engaged, or depressed people are?

And what’s the point of a strong economy anyway? Ultimately, it’s to improve well-being – at least to a large extent. In many ways, then, economic indicators are a stand-in for happiness.

That makes some sense. The richer you are, the more options you have. The easier you can meet your basic needs like food, shelter, and warmth. And the more options you have in general in your life.

Centuries ago, when these basic needs were not as well met as they are today, a concern with the economy made a lot of sense. But today, we’ve basically got that covered.

That’s not to say we should throw them all out. It’s just that they don’t correlate as strongly with well-being as they perhaps once did.

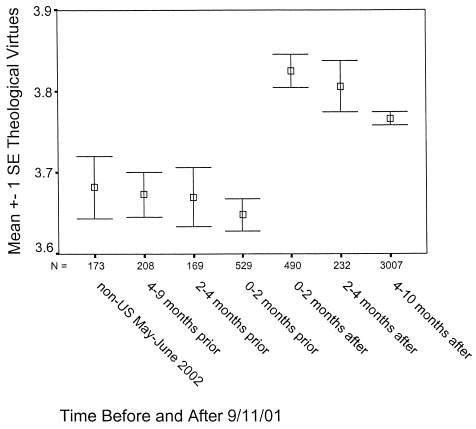

For example, Diener and Seligman argue that in the 50+ years before the paper was published in 2004, GDP had increased steadily. At the same time, however:

- Measures of well-being had remained relatively flat

- Rates of depression had increased 10-fold

- American children experience more anxiety

- The amount of social connections people have had decreased

- People report less trust in both other people and governments

So why not measure and report on well-being directly?

Limitations of measures of well-being

But it’s not all rosy in the world of well-being measurement. There are some problems here too.

- Multiple constructs: researchers measure different “forms” of well-being: satisfaction, positive emotion, negative emotion, depression – these are not necessarily equivalent.

- Single answer questionnaires: a lot of well-being research just asks one question (How happy are you on a scale of 1-10?). The researchers argue that these are less reliable.

- Data is usually cross-sectional: This basically means a measurement taken at one time. It’s better to measure the same people over time to track trends.

They argue that we need more carefully thought-out measures, perhaps even different measures used with different populations (e.g., a different questionnaire for teenagers than adults receive).

Relevant findings in well-being research

Diener and Seligman then go on to summarise some of the relevant well-being research that could be relevant to policy decisions.

National wealth and well-being

There is a correlation between the two – richer countries tend to be happier. However, Diener and Seligman argue that there are diminishing returns – after around $10k GDP per capita, money makes much less of an impact.

Governance and well-being

Human rights correlate with well-being, as you’d expect. But since richer countries tend to have better human rights on average, it’s hard to say how much of an impact they have by themselves.

Democracy, and greater involvement in the political process, also predict well-being.

The perceived effectiveness and trustworthiness of governments was correlated with well-being.

Political stability is also important, and in the short-term can be more important than the impact of having a democratic government system at all.

Social capital

Social capital in a society means high levels of trust and helping between people.

Community boosts well-being – this can mean volunteering, club memberships, church attendance, and people socialising in general. Basically whenever people get together with positive intentions towards each other.

Trust in a society is linked to higher well-being and lower suicide rates. Recent studies (at the time: 2004), showed declining trust in the United States.

Religion and well-being

Religious people tend to be happier than the non-religious, on average, both across and within nations

Church attendance plays a role here – religion ties into the social capital effect.

Money and well-being

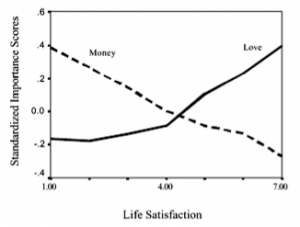

Higher income is linked to well-being, but it’s a slightly more complex situation than the mere correlation implies.

Generally speaking, the poorer the country, the stronger the correlation. For example in the US, the correlation is .13 – it exists, and when we’re talking about policy decisions affecting 300 million people, it matters. But it’s not worth writing home about (about 1.7% of the variance in well-being accounted for by income).

In the slums of Calcutta, however, the correlation is .45 (about 20% variance explained).

Again, this probably comes down to the basic needs issue I mentioned earlier.

The correlation probably goes both ways, also – a number of studies show that happier people do better in the workplace:

- Job satisfaction and positive meed contribute to productivity

- Happier employees change jobs less often and take less time off

- Happier employees are more helpful and have better work relationships

- The well-being of employees can predict customer satisfaction

More on the impact of happiness on work success here.

Materialism and well-being

Also, there might be a negative impact of income on well-being. When people put too much focus on money and material possessions at the expense of other values, they may experience lower self-esteem and well-being.

More on materialism here.

Physical health and well-being

Well-being correlates with health, not surprisingly. Better health means higher well-being.

However, people tend to adapt to health conditions, and once they are used to them and able to cope, their well-being moves towards where it was before they got the health condition, sometimes all the way. However that’s not always the case, especially with illnesses that affect daily life, or which are/could be terminal.

As with money, the health link might also work both ways, to some extent.

- Lifespan is longer in countries with higher well-being and optimism

- The outcome of certain illnesses can be predicted by well-being measures, especially optimism

- People with higher well-being tend to report feeling less pain

- Well-being measures are linked to better immune responses

More on the link between happiness and health here.

Mental health and well-being

As noted earlier, mental health problems in wealthy countries had been increasing, even though they were becoming wealthier.

Depression, in particularly, had increase 10x in the 50 years before the study was published. This is despite much better GDP, better living conditions, the internet, more music and pop culture, better education, and other benefits.

This is the point of a well-being index – economic measures don’t capture this fact. If you used them alone, you’d thing everything was fine.

A few more points. At the time of this study, Diener and Seligman (2004, remember) reported that:

- 50% of a national sample had experience at least one mental disorder in their lifetime, 30% in the last year, and 18% in the last month

- 16% of young adults in a British study were classed as having a neurotic disorder

- Depression is the third highest cause of loss of “quality adjusted lifespan” (ie taking into account the life in the years, not just the years in the life). Behind only arthritis and heart disease, and higher than cancer and diabetes.

Social relationships and well-being

The need to belong is a psychological need, and when we don’t have positive, supportive people in our lives, we tend to feel very bad. The quantity and quality of our relationships are among the best predictors of an individual’s well-being. This was very well established by the research even back in 2004.

Of course, economic indicators of progress miss the impact of social relations completely. In fact it can be worse – when policies are made with only economic indicators in mind, the outcome back be worse relationships.

Some social indicators do exist – crime rates, marriage/divorce rates, gender equality and so on, but they don’t capture the full picture of the amount and quality of relationships that people have.

Systems of Indicators

Economic indicators clearly aren’t doing their job in terms of being adequate gauge of societal well-being.

A number of other large scale well-being surveys are out there, carried out by the EU, Gallup, and others. But these aren’t quite there either.

So what’s the answer?

Well, it’s probably not a single indicator, but a system of them. Which covers a range of different variables, using a range of methodologies.

For example, a wide-scale cross-sectional survey, combined with a subsample studied using the Experience Sampling Method (basically buzzing people in their phones a few times a day to ask how they feel, rather than giving them one big questionnaire at a single point in time).

Such a system of indicators would have to:

- be policy-focused

- fairly represent all stakeholder groups in a nation

- Include broad and narrow aspects of well-being

- Have a set batch of questions that remain stable over time (to allow long-term comparisons), as well as shorter-term scales that can be added and removed as needed

The authors didn’t discuss the specific variables that should be included in such a survey, and left that as a topic for another day.

Well-being instead of money?

The authors conclude by pointing out that we’re not getting rid of money anytime soon. It’s too entrenched into our culture, has a proven track record, and furthermore, well-being isn’t a panacea that’s going to come along and solve everything.

One of the challenges will be finding a balance between the two – building economic stability without negatively impacting well-being in the process, and pursuing well-being without sacrificing the benefits that the money economy has brought.